"From the union of order and art, something good is always bound to come out".

Rafael Leoz

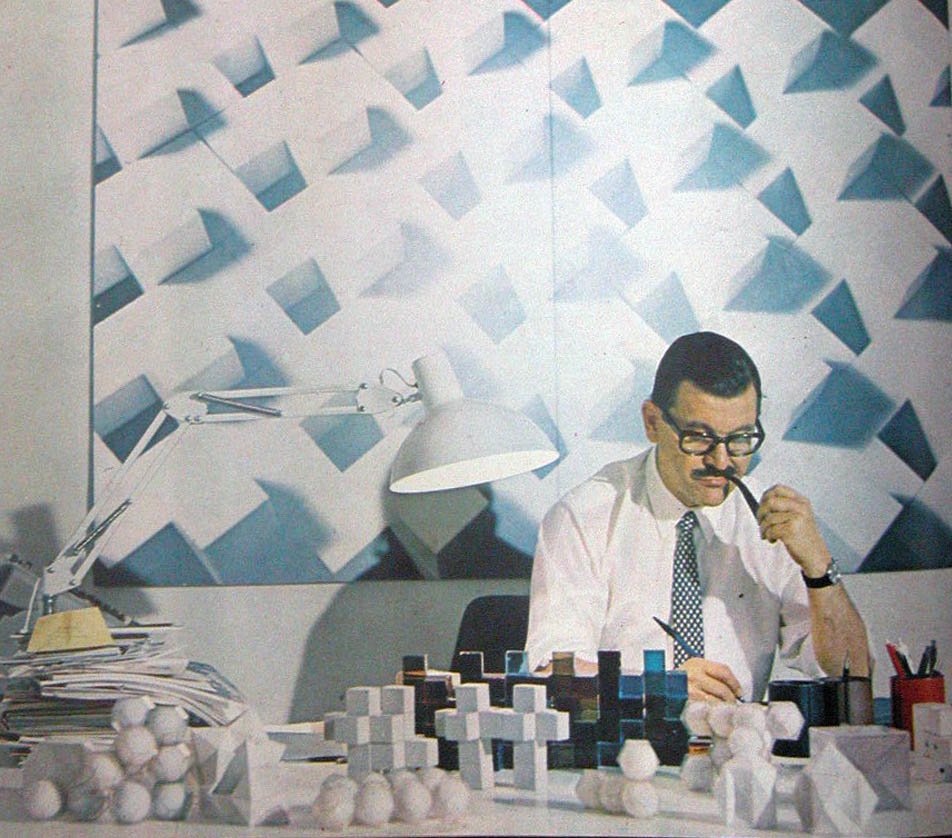

Rafael Leoz de la Fuente’s contribution to the History of Architecture is mainly a theoretical piece of work on geometric modulation and the laws of mathematical harmony applied to architecture, focusing especially on the search for solutions through prefabrication and industrialisation.

Put like that, it sounds verbose and pompous, contrasting with the reality of a man ahead of his time who, without exaggeration, dedicated his work and his life to solving the problem of social housing that had overwhelmed traditional architectural techniques and practices in Spain at the end of the 1950s.

After five years of intense activity in the management of the Poblados Dirigidos project in Madrid, Leoz took a hard but necessary decision to devote his life, literally, to studying and researching. It was a professional crisis turned personal that led him to abandon the execution of architectural works in pursuit of a higher goal, which for him was not an easy option or a mere possibility, but an ‘imperious and inevitable’ decision, as was the process of industrialisation.

It was an obvious but far from easy choice, as Leoz found himself in the midst of the crisis of contemporary architecture, opting for a path which, at least in Europe, was becoming extinct. This was a brave decision, even more so than the architect could have imagined, as his courage cost him a historiographical vacuum in the majority of the Spanish profession of his time, although it was more than compensated for by international recognition.

Despite Leoz’s relevance, after his death, his vital achievements and especially his theories gradually fell into oblivion in the eighties and nineties. One of the reasons for this was that he was one of the architects present in the life of Franco’s Regime and had shone during the Dictatorship. The political transition brought with it a cultural transition, a change of values and perspectives that ended up devouring Leoz’s proposals and plunging them into an undeserved silence.

As the historian Jesús López Díaz concludes in his thesis on the architect, “Oblivion is not a fair price for so much effort”.

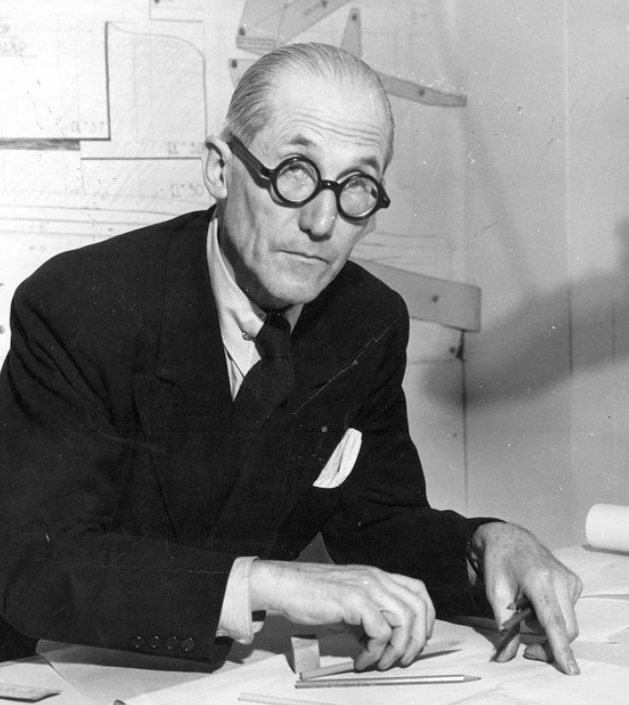

It is therefore only fair to shed light on the studies of Rafael Leoz, a theoretical work that is still cited today in many schools of architecture as an example of research in the field of architectural modulation on the same level as the theories of Le Corbusier and his Modulor. It is no coincidence that Leoz’s work gives continuity to the ideas of the immortal Franco-Swiss architect like no other architect and researcher of architectural modulation, given that his theoretical ideas were in line with those of the German architects of the Deutsche Werkbund and the Bauhaus as well as Le Corbusier’s “machine of inhabitation”. It is therefore also no coincidence that the two became close friends as soon as they shared their ideas, a bond that would last until Le Corbusier’s death.

Le Corbusier y Leoz met thanks Prouvé, who also introduced him to the circle of Swiss architects and industrialists.

He had met Prouvé through José Antonio Coderch, who clearly saw in the Spaniard a connection with the work of other international architects. He was not wrong.

Le Corbusier went so far as to declare that Leoz would become one of the most important architects of the future, and the designer Prouvé expressed his excitement at the idea of industrialising construction as a solution to the housing problem in this way: “Enthused by the initial mathematical rigour, from which an almost infinite expansion could logically be deduced, Leoz’s projects stirred the builder in me and I immediately realised that it was possible, that it could be done!”

This is how he expressed it in the prologue to Leoz’s books, Redes y Ritmos Spaciales (Spatial Networks and Rhythms). Moreover, Prouvé reserved an important space for the architect in his classes at the Centre National d’Arts et Métiers where he explained to his students the theories that had impressed him so much.

Prouvé’s continuous, and at times excessive, praise became Leoz’s constant introduction, as did Le Corbusier’s, who described him as “a genius of architecture, Leoz will become one of the most important architects of the future, the man who has penetrated the essence of architectural composition in the purest way”. “His glasswork reveals a whole theory of colour, his mosaics a theory of rhythm and form.What Leoz has done is astonishing!” Leoz’s admiration for Le Corbusier’s theories was more than repaid when Le Corbusier, one of the most influential architects of the 20th century, was proud to have worked for forty years in the same direction as Leoz and was pleased to think that perhaps his past work had influenced Leoz’s work.

"...A genius of architecture, Leoz will become one of the most important architects of the future, the man who has penetrated the essence of architectural composition in the purest way...his glasswork reveals a whole theory of colour, his mosaics a theory of rhythm and form… He has found the contemporary laws of rhythm and harmony based on mathematics. With him, uncertainty disappears. What Leoz has done is astonishing!”

Le Corbusier

And so it was that these initial contacts quickly became solid friendships and the architect’s greatest supporters, and how they helped to make Leoz and his philosophy known abroad.

His travels to give lectures, ranging from the Polytechnic Institute in Zurich to almost all the Ibero-American capitals and even to American universities such as Harvard and Columbia in New York, attest to the reception Leoz’s ideas received beyond our borders.

It was this international recognition that kept Leoz on a steady course.

So, while new Spanish architects were abandoning social architecture as they gained prestige and recognition, Leoz remained faithful to his idea of improving social housing. It was this altruistic objective that led him to be nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1968, not only for his quality as an architect and the importance of his philosophy, but also for his undeniable human qualities. His nomination was promoted by the Bolivarian Society of Architects on the grounds that Leoz was “one of the contemporary researchers of habitable space who has contributed most to the creation of a new methodology for the organisation and harmonisation of the elements that give rise to architectural spaces within the industrial technique of construction”. The document promoting his candidacy described Leoz’s solutions as “the best safeguard to avoid the dehumanisation of architecture” and that

“the social importance of his work is so great that it has repercussions on the ideals of the human race, so closely linked to the overwhelming world problems of health, education and mass housing, and significantly contributing to the desired peace among men”.

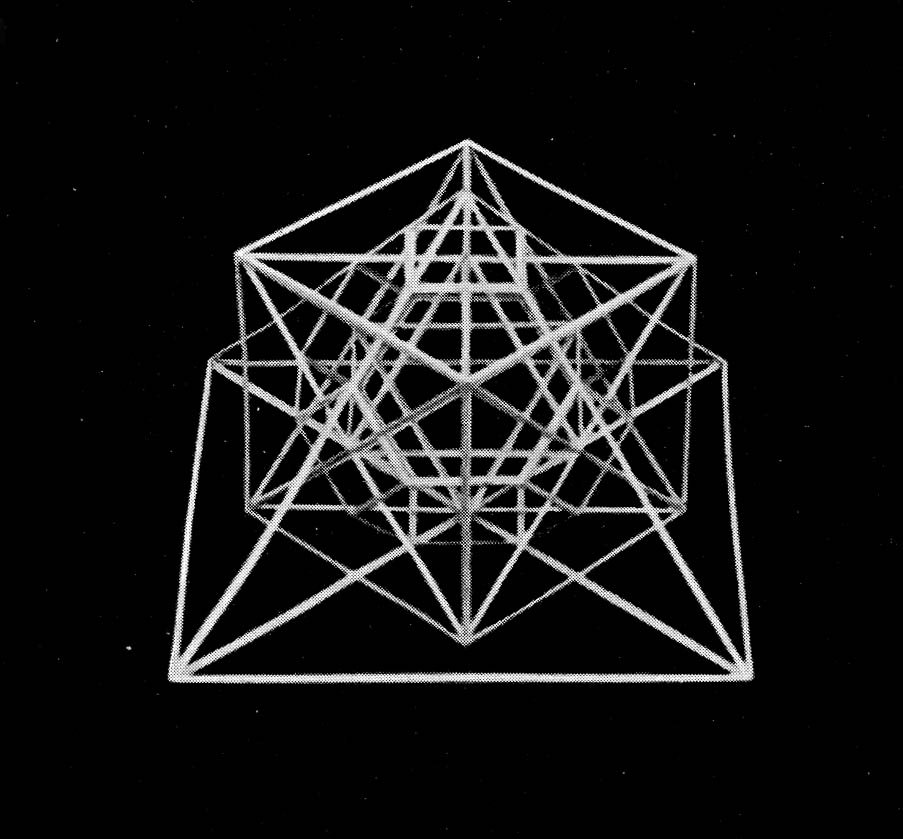

Sculptures by Rafael Leoz

Illustration by Luis Bedoya

Sculptures by Rafael Leoz

While that nomination was in itself a great recognition of Leoz’s work, it was also a confirmation of the enormous distance and asymmetry in the image of the architect in Latin America and in his country of origin.

The History of Architecture tends to prioritise the built over the designed and this, added to Leoz’s premature death, placed him in the category of utopian architect. But nothing could be more inaccurate. Leoz glimpsed a new future for architecture and felt, at least in the mid-sixties, the proximity of that future. Leoz was not naive, he was a mathematician who worked with society in mind, driving research and making global proposals to solve urban and housing problems. Leoz was not a dreamer, at least not as far as architecture was concerned. Leoz was a visionary who knew how to intuit the bases of some laws that structured architectural space.

And that was Leoz’s great discovery: a path towards spatial laws applicable to architecture. Spatial and modular laws that were only the tip of the iceberg. Other architects had already intuited this path, but in order to follow it, a profound investigation was necessary, which required a mathematical training that many lacked and of which Leoz was a great connoisseur. This is what Le Corbusier stated when he said that Leoz had “found contemporary laws of rhythm and harmony based on mathematics. With him, uncertainty disappears”, Jean Dubuisson, President of the ‘Cercle d’Études Architecturales’, agreed with Le Corbusier, when he said that:

“Leoz’s work will mark a milestone in the history of architecture. His theories are so universal that, at first, they are difficult to understand in their full scope. Then, almost immediately, one is astonished by their depth. Everything is perfect and harmonious and obeys a supreme law”

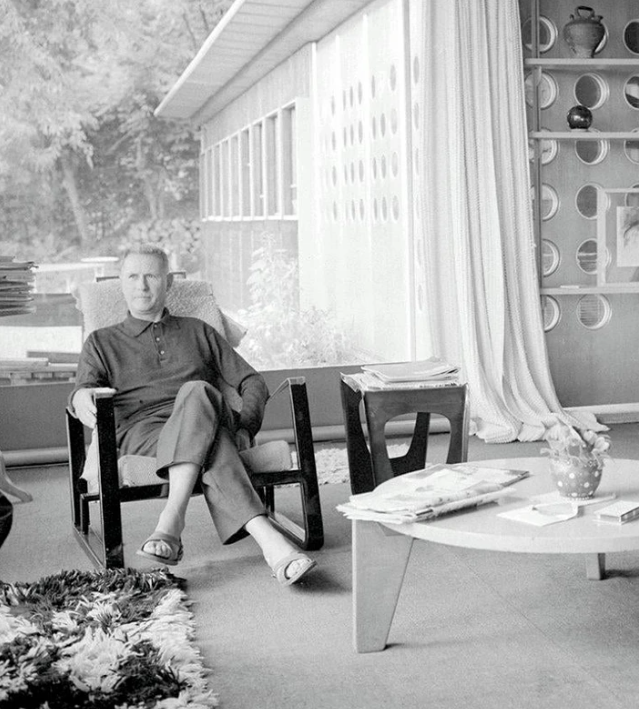

The Leoz Ayuso family

CURRICULUM VITAE

Son of Galo Leoz Ortín and Emilia de la Fuente Patiño.

Married to Maria del Carmen Ayuso Menéndez.

They had four children: Carmen, Rafael, Galo and Maria Ignacia.

He is born in Madrid on 19th June

Graduates as an architect from the Escuela Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid.

Begins his professional career working in collaboration with his classmates: Jose Luis Iñiguez de Onzoño, Antonio Vazquez de Castro and Joaquin Ruiz Hervás, building social housing.

With said classmates he wins second prize in the competition for the Spanish pavilion at the Brussels Universal Exhibition.

Honourable mention in the competition organised by the Asociación Técnica del Derivado del Cemento (Technical Association of Cement Derivatives) for works made preferably with elements based on this material.

First Prize in the Ideas competition organised by the Commission for the development of the Plaza Norte in Madrid.

First Prize in the competition for the development of the Plaza de la Quintana in Madrid.

With these five years of experience, he realises that the housing problem has gone beyond traditional architectural techniques and practices. That he has to abandon craftsmanship in the field of construction for the sake of volume and that he has to fully enter into the heart of industry.

In this year he abandons the practice of his profession and devotes himself to investigating the problems posed by the industrialisation of the construction process, finding laws of harmony which have their roots in classicism and which, through mathematical invariants, open up unlimited horizons in the future of architecture as a fine art.

Aware that he has found solutions, he presents his work on the ‘Division and Organisation of Architectural Space’, which gave rise to the so-called ‘Módulo Hele’ at the 6th Sao Paulo Biennial, where he receives a Special Honourable Mention.

In Zurich he gives lectures as a visiting professor at the Polytechnic Institute, and in Belgium at the Belgian-Luxembourg Steel Information Centre and at the National School of Architecture and Visual Arts in Brussels.

In this year he is invited to give lectures at:

Columbia University, New York.

The Federal Faculty of Architecture in Rio de Janeiro.

Mackenzie University, Sao Paulo.

At universities and professional centres in Venezuela, Mexico, Colombia, Peru and Argentina.

In the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon, three conferences on modern architecture.

At the Polytechnic Institute in Munich and at the Conservatoire d’Art et Metier in Paris.

He is appointed lecturer at the Madrid School of Architecture.

He writes his book ‘Redes y Ritmos Espaciales’ (Spatial Networks and Rhythms) which is published in 1968.

In January he is awarded the Knight’s Cross of Isabella the Catholic.

In March he is awarded the Grand Cross of Civil Merit.

During this year he gives lectures in practically all the Spanish universities and professional organisations.

He is made an honorary member of the Bolivarian Society of Architects.

At the IX UIA Congress in Prague, he receives the First Prize for Greatest Architectural Interest for his film describing his ‘Módulo Hele’.

He is awarded the International Prize ‘La Madonnina’, established by the City and County Council of Milan.

In December, after a lecture he gave in Lima, he is made an honorary member of the Peruvian College of Architects, and President Belaunde Terry bestows on him the Grand Cross of the Order of the Sun of Peru.

The Bolivarian Society of Architects and other countries nominate him for the Nobel Peace Prize.

In March of that year he is a visiting professor at the Centre for Architectural Studies in Brussels.

On 6 February the ‘’Fundación Rafael Leoz para la Investigación y Promoción de la Arquitectura Social‘’ (Rafael Leoz Foundation for the Research and Promotion of Social Architecture) is established. A private institution, classified as a charitable-educational institution by the Order of the Ministry of Education and Science, dated 28th August 1969. The aim of the Foundation is the experimentation of new systems of Social Architecture.

On 18 April the Foundation’s Board of Trustees appoints him Honorary President for life and later General Director.

At the X World Congress of the UIA held in Buenos Aires, he receives the highest award for the film ‘’Arquitectura hacia el futuro‘’ in which the latest research carried out by the Foundation’s team under his direction is featured.

On 3rd February, work begins on the Spanish Embassy in Brasilia.

He is appointed a member of the committee of the World Urbanism Day Organisation in Caracas.

He begins to write his book ‘Arquitectura Molecular Hiperpoliédrica’ (a book he leaves unfinished).

He is appointed by the Compañía Telefónica Nacional de España, Elective Patron of the Fundación Social de las Comunicaciones ‘FUNDESCO’.

He is appointed President of the Technological Studies Commission of the Spanish Institute of Political Studies.

He is awarded the Silver Medal of the Telefónica Company.

He begins to build 218 experimental homes in Torrejón de Ardoz.

His work is exhibited at the Sao Paulo Biennial as part of the Exhibition of Winners of previous Biennials.

On 9th April, by Royal Decree of H.M. Juan Carlos I, he is awarded the Gran Cruz de la Orden de Alfonso X el Sabio (Grand Cross of the Order of Alfonso X the Wise). This decoration was presented to him personally in Brasilia by the President of the Institute of Hispanic Culture, H.R.H. the Duke of Cadiz, on 29th April at the inauguration of the Spanish Embassy.

He dies in Madrid on 28th July.